By Dr. Robert White

John Calvin is, by any standards, a major figure in the history of the Christian church. Almost thirty years younger than Martin Luther, ‘father’ of the Reformation, and his Swiss counterpart, Ulrich Zwingli, Calvin belonged to the second generation of Reformers among whom he exerted an influence second to none.

Born in Picardy, north-west France, in 1509, he had a thorough education in the humanities in Paris, at a time when Luther’s ideas were beginning to enter France. Following law studies at the Universities of Orleans and Bourges, he was converted in around 1533 when, as he himself says, ‘God took me from the miry depths, tamed my heart and made it teachable’. Like some before and many after him, he fled persecution in France and, while passing through Geneva in 1536 – he was then 27 – he was, with difficulty, persuaded to stay and to minister to the infant Reformed church, which was barely a year old.

From 1536 onward, with the exception of three years spent in Strasbourg, Geneva was to be Calvin’s permanent home. These were exceptionally busy years. He was first and foremost pastor and preacher; in addition to his extensive Bible commentaries, he lectured to seminary students, kept up a wide correspondence, composed treatises defending the evangelical faith, trained and sent missionaries into France and, like Luther, took an active part in Bible translation. Throughout these years, too, he continued to revise and to add to his major doctrinal work, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, which grew from a modest six chapters in the first edition of 1536 to a massive eighty chapters in the last edition of 1559. He died in 1564.

The nature of the Institutes

As Calvin explains in his preface to the first edition of the Institutes (1536), the work was written in order to satisfy those who, ‘hungering and thirsting for Christ’, as yet knew little of Christian truth but who, by learning the essentials of the faith, ‘might be trained in true piety’. As the work progressed, however, the objections of powerful opponents and the needs of a growing Reformed community prompted Calvin to attempt a systematic survey of biblical doctrine, suitable not only for the lay person but also for students of theology keen to understand Scripture and to serve God’s church.

A second edition of the Institutes thus followed in 1539, written, like the first, in Latin, but two-and-a-half times longer. Seeking to reach a wider audience, the Reformer translated the 1539 Institutes into French in 1541. Thereafter every successive Latin edition had its French counterpart, up to and including the definitive (Latin) edition of 1559, which appeared in French in 1560. The final edition of the Institutes consists of four books, which speak successively of God the Creator , Christ the Redeemer, the means by which we receive God’s grace in Christ (regeneration, justification, prayer, election), and the external means of grace (church, ministry, the sacraments, discipline).

While, for scholarly purposes, the final edition of the Institutes is bound to have priority, its sheer size inevitably limits its usefulness as an introduction to and exposition of Christian doctrine. Already Thomas Norton, the first English translator of the Institutes (1561), called the work in its final form ‘a book of great hardness, interlaced with Schoolmen’s controversies’. Numerous attempts have been made, both then and since, to reduce the work to more manageable proportions.

For my own purposes, having translated the 1541 French text into English (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2014), I find the second edition of the Institutes of 1539/1541 a convenient and satisfactory point of entry into Calvin’s theology and thought. Such was its value that much of it was incorporated with little change into the definitive edition of 1559. The work is comprehensive without being exhaustive, and omits nothing that is essential to the Christian faith. It ranges widely over the doctrines of God and of man, the law, faith, repentance, justification and works, predestination and providence, prayer, the church and sacraments, civil government and the Christian life. It is refreshingly free of the technical discussions and polemical developments which make the definitive Institutes a daunting read. Assuming, then, that the 1539/1541 Institutes represent Calvin at his lucid best, what do we find when we examine them?

The Institutes: an overview

Historically speaking, two things stand out. The first is the Reformer’s debt to the Church Fathers of the third, fourth and fifth centuries, notably Augustine and Chrysostom. The Fathers were by no means infallible, but they proved helpful allies in Calvin’s endeavour to show that the evangelical faith was not a chicken newly hatched from Luther’s egg. On occasion the Fathers express vital truths with wonderful economy. In the second place, we are reminded of the broad front on which Calvin was obliged to fight. On the right was Rome’s formidable orthodoxy, refined by Scholastics of the quality of Lombard and Aquinas, and super-refined by their less gifted followers. On the left was a myriad of dissenting movements – Anabaptism, spiritualism, antinomianism, antitrinitarianism, and the most shadowy ‘ism’ of all, scepticism. The opposition to Rome was of course fundamental, but it was not exclusive.

On another, more important, level, the Institutes remind us that there is a good and a bad way to do theology. Speculative theology, which asks questions that Scripture does not answer, or intuitive theology, which works upward from man to God, is bad theology. The human mind cannot fathom the unfathomable: Calvin is adamant that only God can reveal God, and in words that accommodate themselves to our weakness. Since, through sin, we fail to recognize God in his works of creation and providence, we must seek him in the written word of Scripture, whose witness is confirmed and sealed by the Holy Spirit. Nor is Scripture a convenient peg on which doctrine may be hung, more or less at will. It is the indispensable foundation on which doctrine rests, the standard by which it is judged and the rule by which it is corrected.

While election figures prominently in the Institutes as central to the plan of salvation, it is presented as an act not so much of God’s power as of his merciful providence. By itself, election does not exhaust Calvin’s understanding of redemption. The Institutes, faithful to the New Testament witness, lay much stress on the humanity of the Son of God. The necessity of the incarnation is driven home by a series of rapid questions. How could the Son mediate between God and man ‘if he were not our close neighbour, allied to us, a high priest able to pity our infirmities’? How could we be confident that we were God’s children, without the guarantee that God’s Son ‘took his body from ours, flesh of our flesh and bone of our bone, to become one with us’, making ours by grace what was his by right? Who could make satisfaction for sin before a just and holy God, but the one ‘who bore the penalty for sin in the very flesh in which sin had been committed’? How could death be endured, ‘except by one who is Man, and be overcome except by one who is God’? Only by embracing Jesus Christ can we know God as Father. Only as the Son consents to be our brother does his Father become ‘our Father’. Made one with Christ by the Spirit’s regenerating power, we are adopted into God’s family and enjoy a relationship which nothing can break – a relationship which we share with all who are Christ’s. ‘If we love Jesus Christ we will love him in our brethren.’ The Institutes are thoroughly Christ-centred.

On the cardinal doctrine of justification Calvin is at one with all the mainstream Reformers. For Christ’s sake believers are accounted righteous by grace through faith. However, grace which renders us blameless before God but which leaves sanctification to us is not grace in all its fullness. While the pursuit of holiness is incumbent on every Christian, the author of the Institutes insists that justification and sanctification are inseparable, though distinct. God’s will, he writes, ‘was to sanctify us by the offering of Jesus Christ made once and for all’ (Heb. 10:10). ‘By sharing in Christ,’ he affirms, ‘we are no less sanctified than justified.’ Our sanctification is therefore complete in Christ and should be manifest in all our works. That our works habitually fall short should drive us continually to repentance, to prayer, to more earnest effort, but not to despair. Christ, who is our wisdom, righteousness and redemption, is also our sanctification (1 Cor. 1:30).

The crux of the Institutes

Do the Institutes convey one lesson more than another? I believe that they do, in the way in which they link knowledge to believing, believing to being, and being to hope.

We noted earlier that Calvin’s essential aim in composing the Institutes was not only to give his readers a basic understanding of Christian truth, but ‘to train them in piety’. That message is reinforced by the subtitle chosen for the French edition of 1541: ‘The Institutes …, comprising a sum of piety, and almost all that needs to be known about the doctrine of salvation’. The order is clear: piety – godliness – before knowledge. Faith cannot exist without knowledge, but knowledge by itself is neither saving faith nor transforming faith. Doctrine must descend from the head to the heart and take root there. It must, under God, change the way we think, feel, will and act; it must change the kind of people we are.

But just as knowledge cannot stand alone, neither can faith. It must be buttressed by hope if it is calmly to judge the events of this life. It is hope which orients faith toward the resurrection life which is ours now, but ours not fully yet. ‘Hope,’ writes Calvin, ‘keeps faith from stumbling in its excessive haste; it leads it to its final goal so that it does not falter in mid-course, but gives it continual strength to persevere.’ Hope makes heaven an ever-present reality.

The author of the Institutes is intensely pragmatic in the way he goes about his work. There is much of the preacher in his evident desire to apply the truths he teaches. Not doctrine only, but its practical outworking is his abiding concern. Thus he defines prayer as conversation with God, in which we give thanks to the Father for his constant goodness and ask him for what we need, praying with both perseverance and regularity, ‘as when we get up in the morning, before starting work, at meal times and when we take our rest at the end of the day.’

Calvin’s practical concern is seen also in his reluctance to debate the issue of Christ’s ‘real presence’ in the Lord’s Supper, and in his wish instead to show how participation in the sacrament nourishes our faith and strengthens our fellowship with the Saviour. It is seen, further, in the affront he feels at the Roman Catholic doctrines of confession and satisfaction, whereby the penitent is required to rehearse all his sins and to recompense God for his wrongdoing. What rest, Calvin asks, can troubled consciences have when they must remember every single offence, past and present, and atone for all of them in full? How much confession or satisfaction is enough?

The Institutes provide sound and sensitive pastoral advice for those who are suffering adversity and affliction, who flinch at the prospect of death, who find it hard to reconcile God’s goodness with the reality of evil or who cannot bring themselves to trust his promises. There is encouragement for the deeply disappointed, for those who feel that life has passed them by. For believers who fear to come before a holy God, there is the assurance that ‘the only judgment seat before which we will appear is our Redeemer’s.’ Christians, that is, have already met their judge and have been fully pardoned. And for the totality of believers ashamed of the immense gap between what they say and what they do, the Institutes have a salutary reminder: what little there is of good in us and in our works is entirely of God. Through the Spirit’s renewal, says Calvin, we have the resources to do better: ‘by grace God honours the works of his grace.’ As always, the last word belongs to God and not to us. That is one good reason among many others why we need to know Calvin’s Institutes.

A note on reading the Institutes

I do not know anyone, however keen, who has had the time or stamina to read through Calvin’s Institutes more or less without interruption. Even in their more concise 1539/1541 form, the Institutes are a big read. The seventeen chapters of The Banner of Truth edition cover over 800 pages. My own practice is to delve selectively into individual chapters according to my current interests and the needs of the moment. The larger chapters are best read in segments or blocs. The Banner edition has useful sub-headings which identify the issue(s) under discussion, and which allow the reader to follow the progress of Calvin’s thought point by point. I would suggest that readers approaching, let’s say, the 1539/1541 Institutes for the first time, begin with one of the shorter chapters – Chapter 7, for example (‘The Similarity and Difference between the Old and New Testaments’), which convincingly demonstrates the unity of God’s covenant mercies under both law and gospel, and the wide sweep of his purposes of grace. Or Chapter 17 (‘The Christian Life’), with its down-to-earth discussion of what it means to live – and die – in and for the Lord. But wherever readers choose to start, they will be amply rewarded, finding much to stimulate thought and to warm the heart.

Dr Robert White was formerly Senior Lecturer in French in the University of Sydney (Australia). His major interest was, and continues to be, Calvin and, more generally, Reformation studies. In retirement, he has translated for The Banner of Truth publishers, Edinburgh, a number of Calvin’s sermons on the Gospel Harmony, on Sermons on 1 Timothy, Sermons on 2 Timothy, and Sermons on Titus, in addition to the French text of the Institutes of 1541. His doctorate is from the University of Paris.

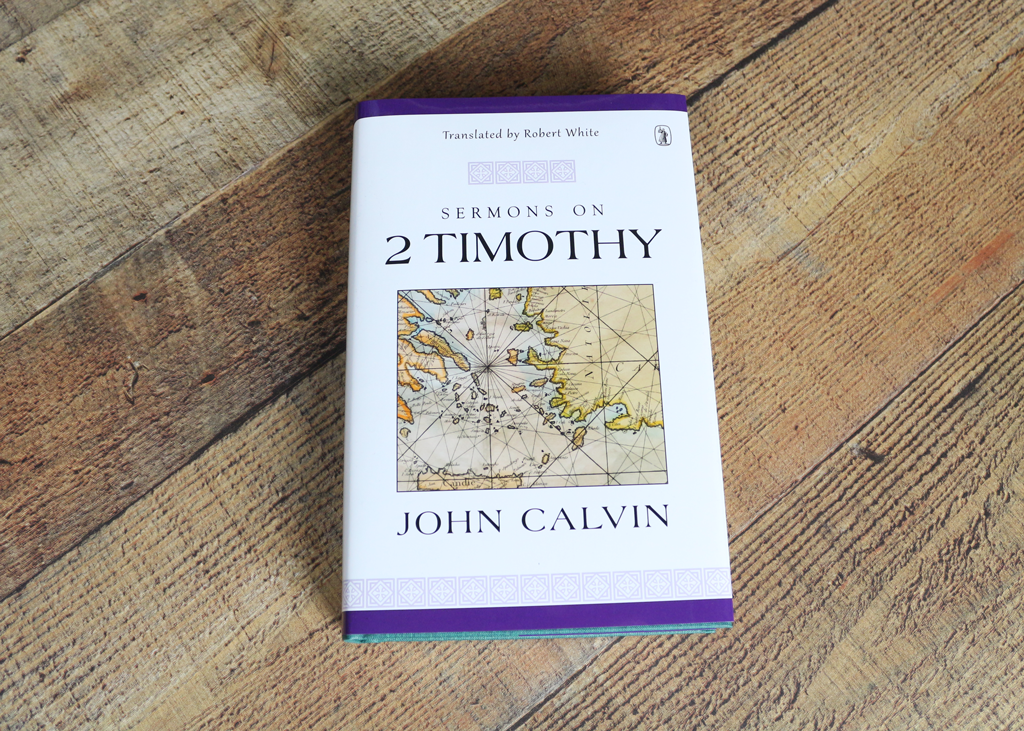

Win a Copy of Calvin’s “Sermons on 2 Timothy”!

The good people at Banner of Truth are allowing us to give away 2 copies of Robert White translated version of John Calvin’s Sermons on 2 Timothy – To enter: Tag Follow and tag us (The Laymens Lounge) and Share this post on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. I hope you win (Contest ends March 27, 2020)!

Throughout his long ministry in Geneva (1536–38, 1541–64), Calvin was a tireless preacher. He spoke of course to a specific congregation and at a particular point in time. Even so his sermons have travelled well across both time and space. God’s word is not bound by history or geography, and Calvin’s French has a robust plainness and directness which allows it to cross barriers of language and culture with relative ease.

Of the 101 sermons which the Reformer preached in 1554–55 on the Pastoral Letters, thirty, on Paul’s second letter to Timothy, are presented here. They have been newly translated from the original French. They offer a clear, forthright exposition of the biblical text, but also challenge the reader to live out the truths taught, since to be profitable God’s word must transform the way we think, feel and act. In Calvin’s hands the sermon is an instrument of real and lasting change.

This volume completes the translation into modern English of Calvin’s Sermons on the Pastoral Letters of the apostle Paul. The companion volumes of Calvin’s Sermons on First Timothy (2018) and Calvin’s Sermons on Titus (2015) are also available from the Trust.

What the Pastoral Letters meant to Calvin may be seen from the unusually frank comment which he makes when introducing his sermon series on Second Timothy:

‘If we read this letter carefully, we will see that God’s Spirit there reveals himself with such power and majesty that we cannot avoid feeling thrilled. For my part, I know that this letter has done me as much good as any book of Scripture. Every day there is something of value in it. I do not doubt that those who closely study it will feel the same. If we want the kind of testimony to God’s truth which will pierce our hearts, we can do no better than tarry here.’

“Calvin’s practical concern is seen also in his reluctance to debate the issue of Christ’s ‘real presence’ in the Lord’s Supper”. What do you mean by reluctance to debate?

Calvin was wrong to use the word “real” presence in the Lord’s Supper. He was admonished by no less than Peter Martyr Vermigli that using ‘real’ presence would cause all sorts of confusion in their debates with the Lutherans. Calvin, instead, should have used ‘true’ presence. Calvin bowed to Vermigli’s wisdom here and bowed out of the debate with the Lutherans until Vermigli passed away in 1562. Calvin would then resume the debate with the Lutherans until his own demise in 1564.

Calvin’s knowledge of the Scriptures and his ability to share that wisdom has always amazed me. I have the 1845 two-volume translation done by Henry Beveridge, forward by John Murray, West Minister Theological. I didn’t know who Calvin was or the Institutes when my pastor gave them to me. I just opened Volume 1 and randomly chose a chapter and the Word of God just jumped off of the page with clarity and completeness. Too bad we don’t have the same level of scholarly attention to the Word as men had back then. One day we can study under the… Read more »

where i can found this book? is it sale.?

You can get it from Amazon here:

https://www.amazon.com/Institutes-Christian-Religion-John-Calvin/dp/1848714637/ref=as_li_ss_tl?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=1848714637&pd_rd_r=dca08940-a083-4028-8b42-e2a2c7e5b139&pd_rd_w=UQIQ2&pd_rd_wg=uEWmu&pf_rd_p=7cd8f929-4345-4bf2-a554-7d7588b3dd5f&pf_rd_r=12DJDYXPGQECC4XJ42WX&psc=1&refRID=12DJDYXPGQECC4XJ42WX&linkCode=sl1&tag=thelaymenslou-20&linkId=87d5c8802c7e5f9c18ad4cc27e056619&language=en_US

but, I beg you that you would buy it for just a few more dollars but support a brick and mortar Christian book store by way of the good people at Hearts and Minds bookstore. Just email them and they will respond quick with the price and details! Here:

https://www.heartsandmindsbooks.com/contact/

thanks

Perhaps I’ve misread the article above, but does it say Calvin was thirty years younger?

Luther was born in 1483. Calvin was born in 1509. So nearly 30 yrs younger.

The first paragraph of Chapter 2 (The Knowledge of Man and Free Will) is not clear to me. Can someone help with this question?

The difficulty arises in the sentence which says, “But the more useful this injunction is, the more careful we must be not to misinterpret it.”

The questions are: what does the “this” refer to? and what does the “it” refer to?

I am reading the Institutes in Beveridge’s translation and am puzzled by his use of old-fashioned English – old-fashioned even for the 19th century. In some places he uses middle-English words and then glosses them, ‘leasings’ for example, which he informs us means ‘lies’. I guess he is working from a much earlier English translation, Thomas Norton’s perhaps? What do you think?