by Steve Bishop & Gregory Baus

“A hundred years after his birth, it has to be said: the lawyer and philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd is the greatest Dutch philosopher of the twentieth century.”

Paul B. Cliteur, president of the “Humanist League” in The Netherlands writing in Trouw (8 October 1994)

Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977) and his brother-in-law Dirk Vollenhoven (1892-1978) developed a neo-Calvinist philosophy more commonly known as Reformational philosophy. Dooyeweerd’s philosophy stresses the sovereignty of God over all reality. God is sovereign as Creator and Sustainer, revealed in the creation, and sovereign as Redeemer in Christ, revealed in Scripture. Dooyeweerd’s philosophy recognizes that although humans have fallen in sin, incurred guilt, and brought corruption to all of life, God’s common grace preserves reality, and His saving grace involves the whole of believers’ lives. As Dooyeweerd wrote:

“God has not abandoned his creation to the spirit of apostasy. The creation is His. It is subject to His absolute sovereignty. For that reason the central dynamic grip of the Word of God affects not only the personal life of the Christian, nor only the church as an institutional fellowship, but all human social relationships, politics, culture, science, and philosophy. “

(Dooyeweerd “A Christian Philosophy: An Exploration” in Christian Philosophy Meaning of History, Paideia Press, 2013, p.2)

Dooyeweerd is an important philosopher, not only because he demonstrated the possibility of a distinctly Christian approach to philosophy and particular sciences, but also because he developed a Christian philosophy, and applied it to his main area of work, law. Others have taken up Dooyeweerd’s approach and insights and applied them to various academic fields, such as mathematics, chemistry, physics, biology, psychology, logic, history, linguistics, sociology, economics, aesthetics, politics, ethics, theology, and to numerous other activities, including soccer, landscaping, information systems, education, sustainability, farming, and others.

Biography

Dooyeweerd was born in Amsterdam on 7th October 1894 to Hermen Dooijeweerd, an accountant, (1850-1919) and Maria Christina Spaling (1862-1948). His father was greatly influenced by Abraham Kuyper. Dooyeweerd was raised in the Reformed denomination in which Kuyper was a leader and attended associated Reformed schools. He was immersed from an early age in Kuyperian thought and neo-Calvinism. Kuyperian themes such as the sovereignty of God, the religious antithesis between regenerate faith and idolatry, a holistic view of the heart, common grace and sphere sovereignty were fundamental to Dooyeweerd’s approach.

In 1912 he enrolled at the Free University (Vrije Universiteit, VU) in Amsterdam – the university founded by Kuyper in 1880 – to study law. In 1917, at the age of 23, Dooyeweerd received his doctorate for a thesis entitled (in English): “Cabinet Ministers under Dutch Constitutional Law”. Over the next five years he worked in various municipal positions.

During this time, he independently studied legal philosophy. He found that there were fundamental conflicts between the different approaches to legal philosophy and this convinced him that there was a need for a “genuinely Christian and biblically based insight and foundation”. In 1918, Vollenhoven, who had been a fellow student at the VU, married one of Dooyeweerd’s sisters. In correspondence with him, Dooyeweerd expressed a desire to “work out the philosophical foundations of science and of developing a theistic position, along Calvinist lines”; in other words, he saw the need for a distinctly Christian approach to philosophy and to all academic disciplines.

In October 1922 Dooyeweerd was appointed the first director of the Kuyper Institute in the Hague, a newly founded research institute of the Anti-Revolutionary Party, the political party organised by Kuyper in 1870 (Anti-revolutionary refers to the French Revolution, particularly its secularism). Vollenhoven had become a pastor in the same city the year before. There Dooyeweerd had time and opportunity to begin developing his philosophical ideas. Early on he recognized that all philosophy and the sciences are dependent on supratheoretical religious beliefs. He continued to work for the Kuyper Institute, for four years. During this time, he produced what came to be The Struggle for a Christian Politics (Paideia Press, 2008). In 1926, Dooyeweerd became a professor of law at the VU, a position he held for 40 years until his retirement in 1965 at the age of 70.

He helped found the Vereniging voor Calvinistische Wijsbegeerte (VCW) (Association of Calvinistic Philosophy in 1935 – it is now called the Association for Reformational Philosophy) –and was editor in chief (1936-1976) of the association’s journal Philosophia Reformata, which is still being published. See a list of some of its English articles here.

To celebrate Dooyewerd’s 70th birthday, G.E. Langmeijer, a president of the Royal Netherlands Academy, wrote: “Dooyeweerd can be called the most original philosopher Holland has ever produced, even Spinoza not excepted” (Trouw, 6 October, 1964).

Dooyeweerd was a prolific author and wrote around 200 articles and books. In 1948 he was inducted into the Royal Academy of Dutch Sciences. The last article he wrote was for Philosophia Reformata in 1975. In 1924, he married Jantiena, and they had 3 sons and 6 daughters. It’s been said Dooyeweerd was socially somewhat shy, but also good-humored, a loving husband and father, enjoyed playing piano, and a keen supporter of Ajax, the Amsterdam soccer team. He died in 1977 aged 82.

Key issues

Dooyeweerd was keen to stress that: “This philosophy is not a closed system. It does not claim to have a monopoly on truth in the sphere of philosophical reflection” (In “Christian Philosophy: An Exploration”, p.4). This meant he knew his views were fallible and could be corrected. He saw the need for his philosophy to be developed, and applied to different disciplines by others. Questions that Dooyeweerd explores include:

- What is meaning? And how are the different ways of meaning related?

- How does a Christian philosophy differ from theology?

- What are the necessary conditions that make theoretical thought possible?

- What view of reality’s origin, unity, and coherence is held by a given philosophy?

- How can we develop a Christian theory of reality?

What follows is a selective overview of a few key issues addressed by Dooyeweerd in his philosophy, including: meaning and creational law, temporal and supratemporal, immanence and transcendence standpoints, theology and philosophy, transcendental criticism, religious ground-motives, modal aspects, and types of things. The brief descriptions are very simplified.

Meaning and law – All created reality, both creational law and all that is subject to it, constitutes meaning. That is, the creation is ultimately dependent on and necessarily expresses and refers back to the Creator. God is the self-existent origin of all things, from, through, and to whom all things exist. Creational law is the boundary between the Creator and the creation. The creation, but not God, is bound to God-given laws and norms. These are not only physical laws and moral laws, nor only laws for sense perception and laws for logic, but laws and norms for every kind of thing that can exist, and every way things do exist and are experienced.

Temporal and supratemporal – Reality as God-given meaning, and our experience of it, has a “temporal” order and duration character that is related to the diverse laws and norms for it, and all that is subject to them. A unity of meaning finds a center of reference in our selves who experience. The unity of one’s self has a “supratemporal” character that is the heart or core of all its temporally diverse expressions and experiences.

Immanence-standpoints and the Christian transcendence-standpoint in philosophy – An “immanence” standpoint is one that takes philosophy’s starting point to be in philosophical thinking itself, however such thinking or its self-sufficiency is conceived. The Christian-transcendence standpoint, however, recognizes that the starting point for philosophy is found in supratheoretical religious beliefs (even for philosophies that take a self-incoherent immanence view).

The relation between Christian theology and Christian philosophy – Philosophy and theology are not distinguished by supposed realms or principles of natural reason and supernatural faith. The term “theology” – as in the knowledge of God – has been used to refer to the (supratheoretical) true knowledge of God in Christ given in regeneration that is eternal life. It has also been used to refer to the (pretheoretical) articles of faith, creed or confession of the institutional church. These senses must be distinguished from each other and from theology as referring to the theoretical study of the teaching of the Bible. In this sense as a theoretical study, theology is a special or particular science and is guided by a general theoretical view of reality that is philosophical. Both a Christian theological science and a Christian philosophy depend in turn on the true knowledge of God in Christ given in regeneration.

Transcendental criticism – Since the so-called Enlightenment era, many suppose it is somehow objectionable to approach the sciences and philosophy (academic fields of study) from a Christian perspective. However, such objections are the result of a competing religious perspective disguised as non-religious or religiously neutral. When the activity of theorizing (or the theoretical manner of thinking that is involved in all these fields) is critically examined its inherent dependence on (supratheoretical) religious beliefs is shown. A ‘transcendental’ critique of theoretical thought is one that examines the necessary conditions that make such thinking possible. This criticism addresses several main points:

a. The difference between pretheoretical experience and theoretical thinking – The ‘everyday’ manner of experience takes reality as it is given in concrete wholes. However, theorizing adds to this everyday experience an ‘artificial’ perspective that highly abstracts kinds of features from experienced reality in order to explain something about it.

b. Characteristics of abstraction and conceptual synthesis -– In abstracting and conceptualizing certain features from reality, the differences between kinds of features becomes apparent in contrast to the logical features of our thinking by which we abstract them. Logically conceptualizing any one kind of feature is only done in relation to the other kinds of features it is also in contrast with.

c. The basis found in self-reflection -– The basis for, or unifying factor behind, our relating such different kinds of features is found in recognizing one’s self as the central reference of all one’s experience of, and thinking about, diverse kinds of features and their coherence.

d. The religious belief in origin – Further, that basis in self-reflection can only be found in terms of what one takes as the origin ultimately behind the coherence of diverse kinds of features and their central unity. Any view of such an origin is not the conclusion of theorizing, but its ultimate basis. And this is synonymous with religious belief.

Ground-motives – A ground-motive is an expression of one of two possible basic religious beliefs or commitments. One of these is characterized by faith in God in Christ revealed in Scripture. The other is characterized by unbelief, or rather by an idolatrous faith in something as the self-existent origin of reality other than God in Christ. As such they are the most fundamental driving forces in human lives and civilizations. They are both a matter of individual belief and commonly held beliefs among communities. There have been four primary historical categories of religious belief influencing Western thought and culture. The three non-biblical religious ground-motives are extremely broad and encompass a great variety of different particular religious beliefs in ultimate tension with each other (and at times in self-conflicted dualism).

- form-matter; (exemplified in Greek thought)

- grace-nature; (exemplified in Scholasticism)

- freedom-nature; (exemplified in Enlightenment and “postmodern” thought)

- creation-fall-redemption (the Biblical Christian perspective)

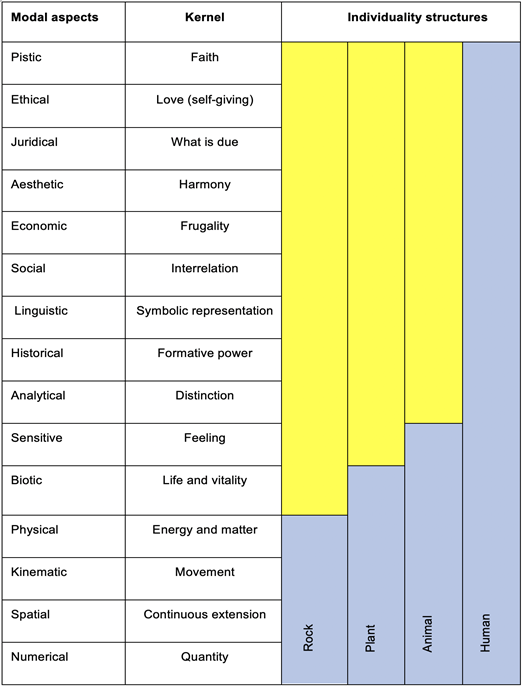

Modal aspects – There are different kinds of features of reality and of our experience of it; different basic kinds of laws, properties, and relations. These are all different “hows”, or ways in which things exist and are experienced. Each modal aspect has a so-called kernel or nuclear core meaning that defines it and its laws or norms, and is irreducible to any other kind of meaning. The list of modal aspects (in Table 1) is a question of empirical analysis and remains open to correction. There has been some debate about the exact number, character and order of the modal aspects, however, the list in Table 1 is well established and broadly accepted in outline.

Every temporal thing functions in all aspects. However, something may function in a given aspect subjectively/actively and/or objectively/passively. For example, an apple tree is “qualified” by the biotic aspect, it is a living thing and functions actively in the biotic and in the earlier numerical, spatial, kinematic, physical aspects. Actively, it is a single tree and has many branches, and (passively) may be counted; it stands in a given place, and (passively) may be located; it has internal movement of sap, and (passively) may be chopped down and removed; it has a material composition, and (passively) may be burned; it is alive, and (passively) may serve the life of other creatures.

However, in the later aspects, an apple tree functions only passively. It cannot feel, but can be sensed (psychical); it cannot think, but it can be distinguished from other things and conceptualized (analytical); it cannot produce culture, but it can be historically formed or cultivated (historical); it cannot speak, but it can be named (lingual); it cannot interact socially, but friends can enjoy its shade while conversing (social); it cannot value or make thrifty choices, but it can be economically valued and used frugally (economic), it cannot make artistic evaluations, but it can be considered beautiful (aesthetic); it cannot commit crimes or sue anyone, but it can be stolen (juridical), it cannot love anyone, but it can be a gift to express love (ethical); it cannot believe or trust, but could be relied upon for fruit or to hold a rope swing – or even be the object of idolatrous worship or recognised as pointing to God as its Creator (pistic).

Table 1. The modal aspects and individuality structures. The blue blocks represent subjective/ active functions; the yellow blocks objective/ passive functions.

Only humans function subjectively/actively in all the modal aspects (see Table 1). In ordinary, everyday (pretheoretical) experience, the modal aspects are experienced in the coherence of their temporal continuity without any explicit theoretical distinction between them. However, they exist in an order of earlier and later, and each modal aspect has analogical connections of meaning to all the others that can be theoretically analyzed. As understood from the biblical Christian ground-motive, none of these ways of existing and experiencing reality is the origin of the others. Rather, all reality, including every way it exists and is experienced, has its origin and holds together in Christ (Colossians 1:16-17). However, theories directed by a non-Christian ground-motive inevitably end up reducing some modal aspects to others and so ‘absolutize’ a given modal aspect (or combination of them), and implicitly take that as the nature of the origin. Christian theories should avoid such reductionism.

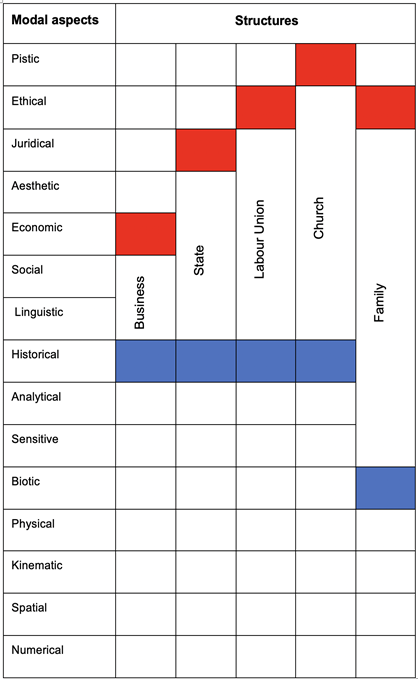

Types of individual things –- In pretheoretical experience we encounter a massive variety of different things and different kinds of things. These include objects, events, processes, actions, relationships, etc. There are both ‘natural’ things, and human-formed things. A thing is qualified by some modal aspect that most characterizes its nature and governs its internal organization. Natural things are qualified by the modal aspect in which they have their highest subjective/active function. Human-formed things are qualified by both a ‘leading’ function in the modal aspect that characterizes and governs the plan by which it was formed, and a ‘foundational’ function in the modal aspect that characterizes and governs the basis on which it is formed. The way a thing is qualified is related to its type law that governs how it functions as that particular kind of thing in all the modal aspects.

Societal communities are human-formed things. They have both a leading and foundational function. Most societal communities have a foundational function in the historical modal aspect, although the family is founded in the biotic modal aspect (see Table 2). The leading functions of different kinds of societal communities accordingly differ. For example, the church’s leading function is the pistic (faith), civil government’s is the juridical (due), a business’ is the economic (thrift), a family’s is the ethical (love). These different kinds of societal communities (or societal ‘spheres’) are normatively related to each other in terms of the principle of sphere sovereignty.

Table 2. Modal aspects and societal structures. The leading function (in red) and foundation function (in blue) of five social structures.

Some key issues not mentioned – Dooyeweerd’s philosophy (not to mention his work in legal science) is quite vast. It’s worth noting that among other key issues, he also addresses: worldview, enkaptic wholes and sub-wholes, historical opening process, philosophical anthropology, the notion of ‘substance’, the meaning of truth, the nature of intuition, and a wide range of issues related to particular sciences or fields of study. Dooyeweerd also critiques a large number of theories proposed by other philosophers and scholars from various periods.

Key writings

The Struggle for a Christian Politics

This book was written originally as a series of articles for the journal Antirevolutionaire Staatkunde (Antirevolutionary Politics) from 1925-26; they represent some of the earliest writings of Dooyeweerd. Here he shows that Calvinism as a worldview has a distinctive starting point which leads to implications for every area of thought and action. In it, he advances the notion that “no Christian politics is possible without a Christian worldview …”.

A New Critique of Theoretical Thought

It was at the VU in Amsterdam that Dooyeweerd completed his De Wijsbegeerte der Wetsidee (WdW) (Amsterdam: 1935-36). This was translated into English in 1953 as The New Critique of Theoretical Thought. This was Dooyeweerd’s magnum opus. There are three main volumes and an additional volume that provides a comprehensive index to the other three.

The first volume examines the presuppositions that make possible theoretical thought and analyses the religious ground-motive of modern humanism as expressed in Descartes onwards. Volume II develops his general theory of the modal spheres and moves on to discuss epistemological issues. Volume III examines “The structures of individuality of temporal reality”. He looks at communities such as the family, the state and the church and discusses what he terms as “enkaptic relationships”.

Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy and The Encyclopedia of the Science of Law

After the New Critique was completed, Dooyeweerd focused on two other major projects – Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy and The Encyclopedia of the Science of Law – so far only volume 1 of 5 of the latter has been translated. The first volume of the Encyclopedia outlines Dooyeweerd’s philosophical approach as it applies to the field of law.

Reformation and Scholasticism volume 1

In Reformation and Scholasticism volume 1, originally published in 1949 he examines Greek philosophy in the light of the form-matter ground-motive. Volume II, published as articles in Philosophia Reformata (1945-1950), examined Greek and Medieval philosophy in the light of the form-matter and nature-grace ground motive. The final volume was uncompleted by Dooyeweerd. It looks at the philosophy of nature and philosophical anthropology (the study of what it means to be human).

In the Twilight of Western Thought

After the Second World War Dooyeweerd travelled extensively to Switzerland, South Africa, France, Belgium, the United States – including several times to Harvard University – and Canada. It was the lectures during one of the tours to North America that formed the basis of In the Twilight of Western Thought (1960).

There are three main themes in this book. Dooyeweerd exposes the pretended autonomy of philosophical thought (Ch 1-2), he looks at historicism (Ch 3-4) and examines the relationship between philosophy and theology (Ch 5-7).

Roots of Western Culture

From 1945 to 1948 he wrote a series of articles in the weekly Nieuw Nederland that formed the basis for his book Roots of Western Culture (1979). In it, he develops the idea of religious ground-motives. It provides a call to Dutch Calvinists to engage in “reflection and renewal” after the Second World War.

Further reading

Works by Dooyeweerd

A full chronological bibliography of Dooyeweerd’s work has been compiled by Harry Van Dyke “A Dooyeweerd Bibliography” (available at: https://www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk/dooyeweerd-bibliography. A list of all Dooyeweerd’s works online is available here: https://herman-dooyeweerd.blogspot.com/

Introductions to Dooyeweerd

Bishop, Steve 2021. Herman Dooyeweerd’s Christian Philosophy (submitted for publication).

Clouser, Roy 2002. Is there a Christian view of everything from nuts to soup?

Clouser, R. A 2010. Brief Sketch of the Philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd. Axiomathes 20:3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-009-9075-2 available here: https://www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk/Clouser/RCBriefSketch.pdf

Gunton, Richard 2020. Two YouTubes on Dooyeweerd’s Secularization of Science part 1 and part 2.

Hayward, Rudi 2020-2021. A series of YouTubes on Roots of Western Culture.

Hayward, Rudi 2020. Tasks and Cosmos: An Introduction to Reformational Philosophy. Available at http://reformationalintermezzo.blogspot.com/2018/01/contents-for-introduction-to.html

Kalsbeek, L. 1975. Contours of a Christian Philosophy: An Introduction to Herman Dooyeweerd’s Thought. Toronto: Wedge.

Ouweneel, Willem 2014. Wisdom for Thinkers. Jordan Station, Ontario: Paideia Press.

Spier, J.M. 1973. An Introduction to Christian Philosophy. Nutley, NJ: The Craig Press.

Roques, Mark (no date) Crocodiles and philosophy

Strauss, D.F.M. 2021. The Philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd. Jordan Station, Ontario: Paideia Press. An earlier version of this is accessible at: https://www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk/Strauss/DFMS2015Dooyeweerd.pdf

Van der Walt, B.J. At the Cradle of Christian Philosophy. Potchefstroom: ICCA.

Wright, Colin 1999. Any Questions: Dooyeweerd Made Easy. (Well easier…). Christianity & Society 9(1): 21-27.

Going Deeper

Chaplin, Jonathan 2011. Herman Dooyeweerd: Christian Philosopher of State and Civil Society. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame.

Choi, Yong Joon 2000. “Dialogue and Antithesis: A Philosophical Study on the Significance of Herman Dooyeweerd’s Transcendental Critique”. PhD Thesis. Potchefstroome universiteit vir Christelike Hoer Onderways.

Clouser, Roy A. 2005 (2nd edn). The Myth of Religious Neutrality. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press

Henderson, Roger 1994. Illuminating Law: The Construction of Herman Dooyeweerd’s Philosophy, 1918 – 1928. Amsterdam: Buijten & Schipperheijn.

Straus, D.F.M. 2009. Philosophy: Discipline of the Disciplines. Grand Rapids, MI: Paideia Press.

Troost, Andree 2012. What is Reformational Philosophy? An Introduction to the Cosmonomic Philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd. Jordan Station, Ontario: Paideia Press.

Verburg, Marcel 2015. Herman Dooyeweerd: The Life and Work of a Christian Philosopher. Translated and edited by Herbert Donald Morton and Harry van Dyke. Jordan Station, ON: Paideia Press.

Web resources

Dooyeweerd pages www.dooy.info – set up by Andrew Basden in 1997. The website aims to aid scholars in understanding Dooyeweerd’s philosophical framework. There are over 300 pages on the site which provide resources to explore, discuss and critique Dooyeweerd.

All of life redeemed (www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk) – set up in 2005 it provides a virtual library of Reformational resources. It has pages devoted to over 80 different scholars who work, or have worked, out of a Reformational approach.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jason Estopinal and Rudi Hayward for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Gregory Baus is writing an M.A. thesis on Herman Dooyeweerd’s philosophy at North-West University in South Africa. He first began studying Dooyeweerd in 1994, and formerly attended the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. His personal interests include classic diners, folk music, and speculative fiction. See his extended bio here.

Steve Bishop is an independent researcher based in Wales, UK. He maintains the neo-Calvinist website www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk and is a trustee of Thinking Faith Network. He earned his doctorate at the North-West University in South Africa (2019). He is the co-editor of On Kuyper (Dordt Press, 2013). He has had articles published in Foundations, Koers, Pro Rege, and the Journal for Christian Scholarship.

Thank you for this overview of Dooyeweerd. I have been intrigued by him and Vollenhoven for a few years since doing research for a chapter I wrote on Kuyper. I find Vollenhoven more accessible and Dooyeweerd much more confusing a writer than Kuyper, Bavinck, Rookmaaker, etc. I realize Dooyeweerd is “another step up” to some extent than the others I mention but in my attempt to make sense of his ideas and find relevance for my own area of philosophical rhetoric, I struggle. This does not mean the end of the struggle to find understanding. I do find people like… Read more »

Mark, on Dooyeweerd’s philosophy, I do especially recommend Clouser’s summary and explication of Dooyeweerd’s views in his book The Myth Of Religious Neutrality, as well as in his articles: On the General Relation of Religion, Metaphysics, and Science the first 12 pages or so of The Transcendental Critique Revisited and Revised A Brief Sketch of Dooyeweerd’s Theory of Reality …among others. However, I (speaking for myself, not Steve) agree with you that Clouser’s (and several other Reformational scholars’) politics and economic views are significantly more statist (‘progressivist’) than Dooyeweerd’s. Dooyeweerd is much more concerned to strictly limit the role and… Read more »

Thank you. I have read Clouser’s Myth of Religious Neutrality— helpful. I will get these other works and continue to dig. Thanks, again.

Podcast (audio article) links:

Google

Amazon

Spotify

PlayerFM

RSS

Outstanding piece of work. I provides an excellent summary and introduction to the thought of Dooyeweerd. The goal of this post is to see if you have any interest in “moving beyond” Dooyeweerd or at least point to a person who shares that vision. I was introduced to Dooyeweerd (HD) about 4 years ago by Roy Clousner. The retired Professor Clousner was kind enough to talk to me and discuss my journey into the world of thought. In fact, he sent me an autographed copy of “The Myth of Religious Neutrality”(which I read and discussed with him). Via Professor Clousner’s… Read more »

Thanks very much, Robert. Of course Steve can speak for himself, but here are a few of my thoughts in reply. I definitely encourage your interest in Reformational Philosophy, and I share your goal of continuing the work and seeking the promotion of it. 1. I wouldn’t exactly speak of a “philosophical expression of Christianity,” but rather of Christian philosophy; that is philosophy grounded in the Christian religion. Such philosophy is a fallible and limited theoretical endeavor, whereas Christianity is the religion revealed by God in the Scriptures. Perhaps you agree. 2. As for the “failure” of Dooyeweerd’s work, I… Read more »