by Steve Bishop

“Groen’s work is significant not only for the past and the present, but also for the future” – Herman Bavinck

“… a fascinating and most important man. … He was on all accounts a most remarkable man.” – D.M. Lloyd-Jones

“Groen cannot be characterized better than a ‘fighter against unbelief’.” – H. Smitskamp

Introduction

Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck were the main instigators of the movement that became known as neo-Calvinism, however, they stood on the shoulders of others. One of these was Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer (1801–1876). Harry van Dyke describes him as a “godfather” to both Kuyper and Bavinck (Van Dyke, 2012); and Bratt describes him as “something of a surrogate father to Kuyper” (Bratt, 2013: 62). He was visited by several abolitionists from Britain. They had heard of his ideas for social reform, they hoped he would become “Holland’s Wilberforce”.

Many of Groen’s embryonic ideas were taken up and developed by Kuyper. These included:

- The necessity of Christian education and “the freedom of religion with respect to our children”

- Sphere sovereignty[1]

- The need for a Christian political party

- The impact of modernism on society, and tied to this

- The negative role of the worldview behind the French Revolution

Groen, an intellectual historian and social commentator, was born into a wealthy aristocratic family. His father, Pieter Jacobus Groen van Prinsterer, a medical doctor, married Adriana Hendrika Caan, the heir to the wealthy Rotterdam merchant family. Like Kuyper and Bavinck after him Groen studied at Leiden University.

Groen the student

At Leiden, he completed two doctoral dissertations, one in the law faculty and the other in the literary faculty. Groen was no academic slouch and completed both doctorates within a year! While at Leiden, he attended the private lectures of Willem Bilderdijk’s (1756–1831). Bilderdijk was one of the key figures in the Dutch Réveil, a pietistic revival that originated geographically in Geneva. Within Bilderdijk’s circle were the poet Isaac da Costa (1798–1860) and church historian J.H. Merle d’Aubigné (1794–1872). Although he was not yet a Christian Groen was influenced by these men. He later said of Bilderdijk he “frightened me off unbelief, [rather] than brought me to faith”.

On graduation in 1823, he was unsure of his next steps. He began work as a barrister in 1824.

Groen the secretary in the King’s cabinet

In 1826 the King invited submissions for a general history of the Netherlands. Groen entered. He was one of five authors who received a gold medal for their submissions. Subsequently, he applied for and was appointed to the post of Secretary in the King’s Cabinet. It was an administrative post that he held for six years – it was not a position that he enjoyed and, as a result, his health suffered. During this time, he courted and married Elizabeth Maria Magdalena van der Hoop (1807–1879) in 1828. They had no children.

At the time Belgium and the Netherlands were united as one kingdom and Groen spent time in Brussels. During his time there he became acquainted with Merle d’Aubigné who introduced him to others in the Réveil movement.

Groen the Christian

Although brought up in a liberal Christian environment Groen had no personal Christian faith until 1833. He was greatly impressed with the baptism of Isaac da Costa. Also, his wife was a Reformed Christian. It was no doubt her prayers and testimony that influenced him. His journey to the Christian faith took several years. It was through his wife that he became increasingly known to those involved in the Réveil.

Groen’s mother died in 1833 and he became increasingly unwell. He travelled to Switzerland to convalesce and there he once more came under the preaching of Merle d’Aubigné.

Groen the journalist

Groen, like Kuyper after him, knew how important communication was. He published a daily newspaper, De Nederlander, from 1850 to 1855 with the intent of reaching the Dutch intellectuals. Later, from 1896, he published a weekly the Nederlandsche Gedachten (Dutch Thoughts/ Reflections). This was a resurgence of the paper he produced from 1829 to 1832.

He also recognised the need for a popular newspaper to educate and motivate the people, so he invested three thousand guilders as start-up money for Kuyper’s De Standaard when it was launched in April 1872.

Groen the historian

Groen was fascinated by history; it was not only an academic interest; he agreed with Bilderdik’s assertion that “In the past lies the present”. In his Christian Political Action in an Age of Revolution, he wrote:

I am enamoured of the past. For sure I am. I do not believe it possible to break with the past. I believe that every notion connected with the future is rooted in the past.

He has been described as the “father of modern Dutch history”. He called his approach a “Christian-historical worldview”.

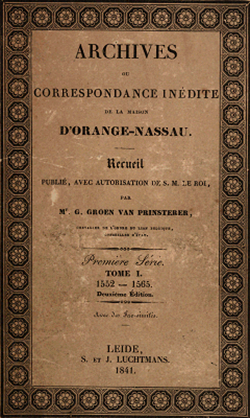

He was appointed to the Palace Archives as an archivist. There he became absorbed in Dutch history and the influence of Christian principles. He published twelve volumes of the Archives ou Correspondance Inedite de la Maison d’Orange-Nassau. These established his reputation as a historian.

He also became concerned about the history lessons schoolchildren received. He produced an overview of Dutch history for the use of teachers to help them improve their teaching. This Handboek der geschiedenis van het Vaderland [Handbook of the History of the Fatherland] was published in 1841 and was finally completed in 1846. It comprised over 1100 numbered paragraphs. A wealthy benefactor financed a fourth printing of the Handbook to enable it to be distributed free to hundreds of Dutch schoolteachers. The book is still in print.

Commenting on Groen’s view of history Schutte has this to say:

To study history, therefore, is for Groen not just a pleasant pastime that can yield many interesting things. It is an essential work for a Christian, who should leave no means unused to learn to know God better. It stands written! It has come to pass! That is how Groen loved to summarize his Christian-historical world-view. Notice how Groen’s aphorism puts Holy Scripture first, as God’s indisputable proclamation of the truth. But God also reveals himself in what comes to pass in history, although on that score human knowledge is limited and imperfect, which is why the book of history will always have to be read while constantly testing it against the written Word. What has happened is not good just because it happened. … The distinctiveness of Groen’s position was that he wanted to apply the standards of God’s law to the historical process—in which, after all, anti-godly, diabolical forces are active as well.

Groen the politician

He was a member of the Dutch parliament on three occasions and was the leader of the Anti-Revolutionary movement. He was elected to the parliament in 1849, 1855 and 1862. In his early days, he described himself as a “conservative-liberal or liberal-conservative”. Later he took a middle position that he described as Christian-Historical. He realised that, as a Christian, he could not align himself with either side. Likewise, he was neither conservative nor progressive.

Groen the school reformer

In 1837 Groen published “Measures Used against the Dissenters judged by Constitutional Law”. In it he argued against forcing parents to send their children to schools that didn’t comport with their worldview was a violation of their God-given right; a God-given right to educate their children in accordance with their religious beliefs. He described the Dutch education system as being un-Christian and anti-Christian.

When his arguments were met with disdain and indifference at best, he realised that more was needed to be done – constitutional reform would be necessary.

In 1860, Groen founded “The Association for Christian National Primary Education”. Its purpose was to promote the founding of schools free from state control. He was a vociferous promoter of free schools without government interference and for equal funding for these independent schools.

Groen the Anti-Revolutionary

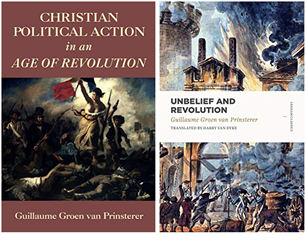

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, revolution was in the air. As well as the French Revolution in 1789, there were revolutionary outbreaks in Greece, Poland, Austria, Germany and Hungary. This revolutionary spirit was the backdrop to Groen’s book Unbelief and Revolution, published in 1847.

Unbelief and Revolution

These fifteen lectures, which were subsequently published, were given to a small group that gathered in Groen’s house in the Hague.

In the lectures, he argued that the spirit of the French Revolution of 1789 lives on. His main thesis was that “the cause of the Revolution lies in unbelief” (Lecture VIII). However, the term revolution was not only a reference to the French Revolution; it also stood for the spiritual and intellectual shift that it brought in. The spirit of secular humanism was damaging the created order for society. Revolution was rooted in a worldview. The birth of modernism took place during this period. The Revolution was as important as the Reformation, but it was the antithesis of the Reformation; it was the Reformation in reverse:

The Revolution is an all-embracing system for religion, law, and ethics; it is a reversal of ideas (by a rejection of revealed truth) in church, state, and society: Social Revolution.

Its cry of “Fraternity, Liberty and Equality”, he thought were important but only if seen through a Christian perspective. The promises of fraternity, liberty and equality resulted in their opposites:

For justice there came injustice; for freedom, compulsion; for toleration, persecution; for humanity, barbarity; and for morality, dependence (Lecture VIII)

Groen drilled down to the starting points and principles of the French Revolution. The first few lecturers examined some key factors; these, however important as they were, were not the main reason:

The principle of this vaunted philosophy was the sovereignty of Reason, and the outcome was apostasy from God and materialism. That such an outcome was inevitable once the principle had been accepted is demonstrable from the genealogy of ideas. … Reason became the touchstone of truth. (Lecture VIII)

Groen the mentor of Kuyper

At first glance, there were many differences between Groen and Kuyper. Kuyper was a theologian by training, a pastor, a polemicist, he was bold and brash, and a populist; Groen was an aristocratic lawyer by training and reserved. Kuyper regarded Calvin as a republican, he saw Calvin as a monarchist. However, despite the surface differences, they had much in common. Both were concerned with the school struggle, both realised that the school struggle would involve political involvement, both were at one point newspaper editors, both rejected the notion of popular sovereignty, but more importantly and both had the gospel of the risen Christ as their motivation.

Groen first became aware of Kuyper in 1864 when Kuyper wrote to him requesting help in finding documents relating to the Polish reformer John à Lasco. The two later began to exchange letters. Groen recommended reading for Kuyper – these included works by F.J. Stahl, Edmund Burke and François Guizot.

Many of Groen’s colleagues and friends were wary of his relationship with Kuyper. However, Groen saw within Kuyper important leadership and organisational skills that he himself lacked. Groen had been described as “a general without an army”. In Kuyper he saw someone who could build and lead an army. Kuyper took Groen’s anti-revolutionary movement and made it into the first political party in the Netherlands. Kuyper took up Groen’s mantle in the setting up of the Anti-Revolutionary Party as the first Dutch national political party.

Groen’s death

Groen died on 19th May 1876. Just before his death, he wrote his “Christian historical Testament” in the Nederlandsche Gedachten:

With the publican’s prayer: O God, be merciful to me, a sinner.

With the wisdom of the Heidelberg Catechism: my only comfort in life and death.

With the shout of joy: I thank God through Jesus Christ our Lord.

With the battle-cry of the Reformation: Put on the whole armour of God, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God. Verbum Dei manet in aeternum: The Word of God endures forever.

With the motto: Not a statesman! A confessor of the gospel. (Cited in Schutte, 2016: 132)

He wanted to be remembered not as a statesman but as a confessor of the gospel. He was a statesman because he confessed the gospel. The gospel shaped all he did.

Bibliography

By Groen

Many of Groen’s mainly French and Dutch publications are available here: https://archive.org/search.php?query=Groen%20van%20prinsterer

Two key works of Groen have been translated into English:

- 2018 [1947] Unbelief and Revolution. (Translated. By Harry Van Dyke). Bellingham: Lexham Press.

- 2015. Christian Political Action in an Age of Revolution (translated by Colin Wright). Aalten, the Netherlands: WordBridge Publishing.

On Groen

- Essen, J. L. van, and Morton, H. Donald 1990. Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer: Selected Studies. Jordan Station, ON: Wedge.

- Freeke, Jan 1999. The life and work of Groen van Prinsterer. Banner of Truth, 430 (July): 17-24

- Friesen, G. 2019. New Research on Groen van Prinsterer and the Idea of Sphere Sovereignty. Philosophia Reformata 84(1): 1-30.

- Langley, McKendree R. 1985. The Legacy of Groen van Prinsterer. Reformed Perspective (Jan.1985): 25-28.

- Schlebusch, Jan Adriaan 2020. Democrat or traditionalist? The epistemology behind Groen van Prinsterer’s notion of political authority. Journal for Christian Scholarship 56(3-4).

- Schlebusch, Jan Adriaan 2020. Decentering the Status Quo: The Rhetorically Sanctioned Political Engagement of Groen van Prinsterer. Trajecta. Religion, Culture and Society in the Low Countries 29(2):141-159.

- Schutte, Gerrit J. 2016 Groen van Prinsterer: His Life and Work. (Translated by Harry Van Dyke.) Neerlandia, Alberta: Inheritance Publications.

- Smitskamp H. 2017. Building a Nation on Rock or Sand. (Translated by Harman Boersema). Ontario: Guardian Books.

- Van Dyke, H. 2012. Groen van Prinsterer: godfather of Bavinck and Kuyper. Calvin Theological Journal 17(1): 72-97.

- Van Dyke, Harry 2016. Groen van Prinstererʹs interpretation of the French Revolution and the rise of ʹpillarsʹ in Dutch society. In Narratives of Low Countries History and Culture,edited by Jane Fernoulhet and Lesley Gilbert. London: UCL Press: 52-62.

- Van Dyke, H. 2019. Challenging the Spirit of Modernity: A Study of Groen van Prinsterer’s Unbelief and Revolution (Studies in Historical and Systematic Theology) Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Recent PhDs on Groen

- Noteboom, Emilie J. 2017. Critical analysis of Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer’s Christian-historical principle, with a comparative critical analysis of his argument of ‘history’ with that of Edmund Burke’s as used in their critique of the French revolution. PhD Thesis, Oxford University.

- Schlebusch, Jan Adriaan 2018. Strategic Narratives Groen van Prinsterer as Nineteenth-Century Statesman-Historian. PhD thesis. University of Groningen.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Colin Wright for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

[1] There is some debate over this. George Harinck maintains that it was Kuyper’s original idea; Friesen maintains that it goes back to Van Baader. Until recently, the consensus has been that Kuyper was influenced by Groen. It may well be that the notion was commonplace among Reformed European Christians though not as clearly articulated as in Kuyper’s work.

Steve Bishop is an independent researcher based in Wales, UK. He maintains the neo-Calvinist website www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk. He is a trustee of Thinking Faith Network. He earned his doctorate at the North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa (2019), supervised by Renato Coletto. He is the co-editor of On Kuyper: A Collection of Readings on the Life, Work & Legacy of Abraham Kuyper (Dordt Press, 2013). He has had articles on Kuyperian neo-Calvinism published in Foundations, Koers, Pro Rege, and the Journal for Christian Scholarship. He blogs here and you can follow him on Twitter

Well done.

I recommend this article by Lucas Freire on the classical liberalism of Groen and Kuyper: https://academic.oup.com/jcs/article-abstract/63/2/197/5825405